God, who knows the force that the commitments linked to this type of pact had among those peoples, agrees to make covenants with men in order to underscore the seriousness of His promises.

A covenant with Noah is mentioned in the book of Genesis (Gn 9,9-17), although in that case it is not a bilateral commitment. It is rather the ratification of a promise made by the Lord that there will never be another flood that destroys living beings on Earth, with no corresponding commitment required on the part of Noah and his descendants.

Also in Genesis, it is said that the Lord made a covenant with Abraham through a ritual in which he promised to give his offspring the land where he lived (Gn 15,7-21) and another, also with him, to ratify the promise of a numerous offspring (Gn 17,2-14), in which circumcision would be the sign of the commitment assumed (Gn 17,11).

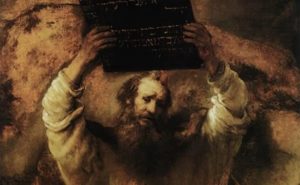

However, the biblical covenant par excellence, the one that constitutes Israel as the people of God, is the one narrated in the book of Exodus after the liberation from slavery in Egypt. On Mount Sinai, God gave the Law to Moses, and the agreement to comply with it was ratified by immolating certain animals and sprinkling the people with the blood of the victims (Ex 24,3-8). The people promised to fulfill everything that the Lord had commanded, and God promised to take care of them as His own people.

Moises with the Tablets of the Law (Rembrandt)

Nevertheless, in subsequent centuries, the prophets record so many sins and betrayals that, as Isaiah points out, “the covenant has been broken” (Is 33,8). For his part, Jeremiah calls urgently for faithfulness to the agreement: “listen to the words of this covenant and put them into practice” (Jr 11,6). But they ignore him. For this reason, because of the repeated infidelities of the people, that covenant is considered broken. Despite everything, a new one is announced, which will last forever: “This is what the Lord God says: I will deal with you as you deserve, because you have despised my oath, by breaking the covenant. Yet I will still remember the covenant that I made with you in the days of your youth, and I will establish an everlasting covenant with you” (Ez 16,59-60; cf. Jr 31,31-33).

The mediator of the Sinai covenant had been Moses. The mediator of this new and eternal covenant is Jesus Christ (Hb 9,14-15). This new Covenant between God and humanity has been ratified not with the blood of sacrificed animals, like that of Mount Sinai, but with the blood of Christ shed on the Cross.

The redemptive sacrifice of Christ is renewed on the altar each time that Holy Mass is celebrated. At the consecration, the priest lends his voice to Christ to repeat in his name the words he pronounced at the Last Supper while holding the chalice in his hands: “Take this, all of you and drink from it, for this is the Chalice of my Blood, the Blood of the new and eternal covenant, which will be poured out for you and for many for the forgiveness of sins. Do this in memory of me.”

By Father Francisco Varo Pineda