Today, the Negev Desert (or Neguev) is visited for several reasons. Its erosion craters, or Makhteshim — the most famous being Makhtesh Ramon — attract geology enthusiasts from around the world. The exceptional clarity of its sky makes the Negev a privileged location for observing the stars. Finally, its proximity to the Arabah Valley — the largest migratory corridor for birds traveling between Europe and Africa, makes the Negev one of the world’s most popular destinations for birdwatching. Some groups of pilgrims will also spend a couple of nights in the Negev to recall and commemorate its biblical history.

The Valley of Zin in the heights of the Negev. Photo: Henri Gourinard.

The Negev, in the Old Testament, appears as an arid place, situated to the south of Jerusalem—or of Judea. Isaiah describes the terrible hurricanes that sweep through it (Is 21:1) before pronouncing an oracle against the animals that inhabit it: lions, vipers and saraphs, wild donkeys and camels (Is 30:6)

Today, the Negev corresponds to the southern cone of the State of Israel, whose borders were fixed by the agreements between Egypt and the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the 20th century. In contrast, the biblical Negev is not a specific place but a vast inhospitable desert on the margins of the Promised Land.

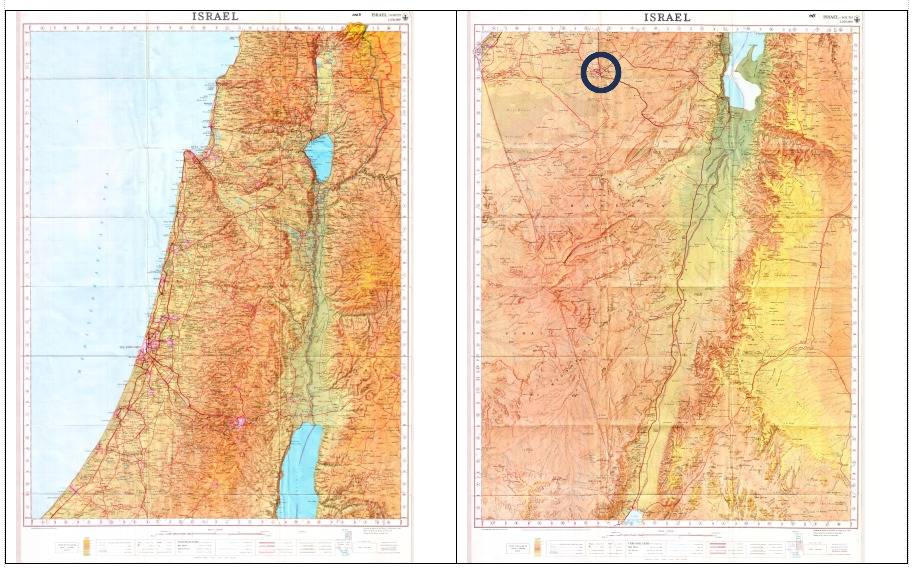

The Negev Desert (map on the right) occupies more than half of the surface area of modern Israel. The modern city of Beersheva was built a short distance from the biblical Beersheba.

Of the 38 occurrences of “Negev” in the Old Testament, 5 are from the book of Genesis and have as their context the story of Abraham and Isaac. Upon returning from Egypt with his wife, Abram — God had not yet changed his name to Abraham —crossed the Negev, reaching as far as the hills of the land of Canaan (cf. Gn 13:1). Subsequently (Gn 13–19), he settled at Mamre, in the environs of Hebron, where the hills meet the plain of the northern Negev.

At the beginning of chapter 20, we see Abraham descend toward the region of Gerar, between Hebron and Gaza, where Abimelech reigned. Although the two communities lived in relative harmony, disputes soon arose between the shepherds of Abraham and those of Abimelech, on account of the scarcity of water. Abraham complained to Abimelech that some of his men had seized one of the seven wells that he himself had dug. The two leaders succeeded in calming the spirits of their own people and reached an agreement sealed by a covenant.

Then Abraham took sheep and cattle and gave them to Abimelech and the two made a covenant. Abraham also set apart seven ewe lambs of the flock, and Abimelech asked him, “What is the purpose of these seven ewe lambs that you have set apart?” Abraham answered, “The seven ewe lambs you shall accept from me that you may be my witness that I dug this well.” This is why the place is called Beer-Sheba; the two of them took an oath there.

Genesis 21:27-31

The gesture of Abraham in setting apart seven (shev’a in Hebrew) sheep intrigues Abimelech. Abraham swore (shav’a) to him that they would be restored to him later as a “testimony” of his good faith. Therefore, this place of the oath made by Abraham took the name of Beersheba (Beer-Shev’a), both because of the number of wells he dug and because of the number of sheep he set apart.

By Henri Gourinard

Tel Sheva is probably the Beersheba of the covenant between Abraham and Abimelech. Its well is located near the city gate, but outside the walls, so that the inhabitants of the city could not seize the water. Photo: Lior Peleh (2019).