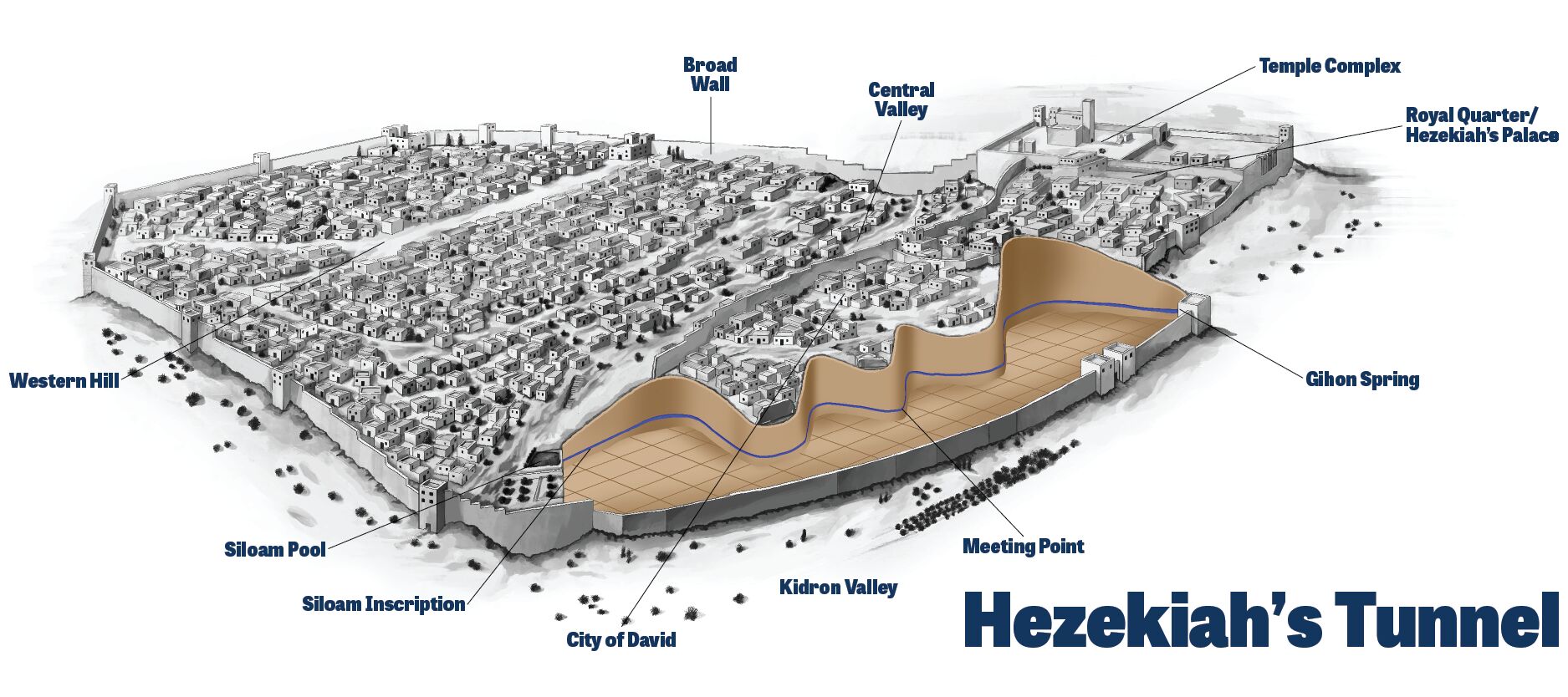

Hezekiah’s Tunnel is one of the most emblematic biblical sites in Jerusalem. Thousands of visitors walk through it each year with their feet covered in water. Its history dates back to the reign of Hezekiah, when the king of Judah had it excavated in preparation for a siege by the Assyrian army of King Sennacherib.

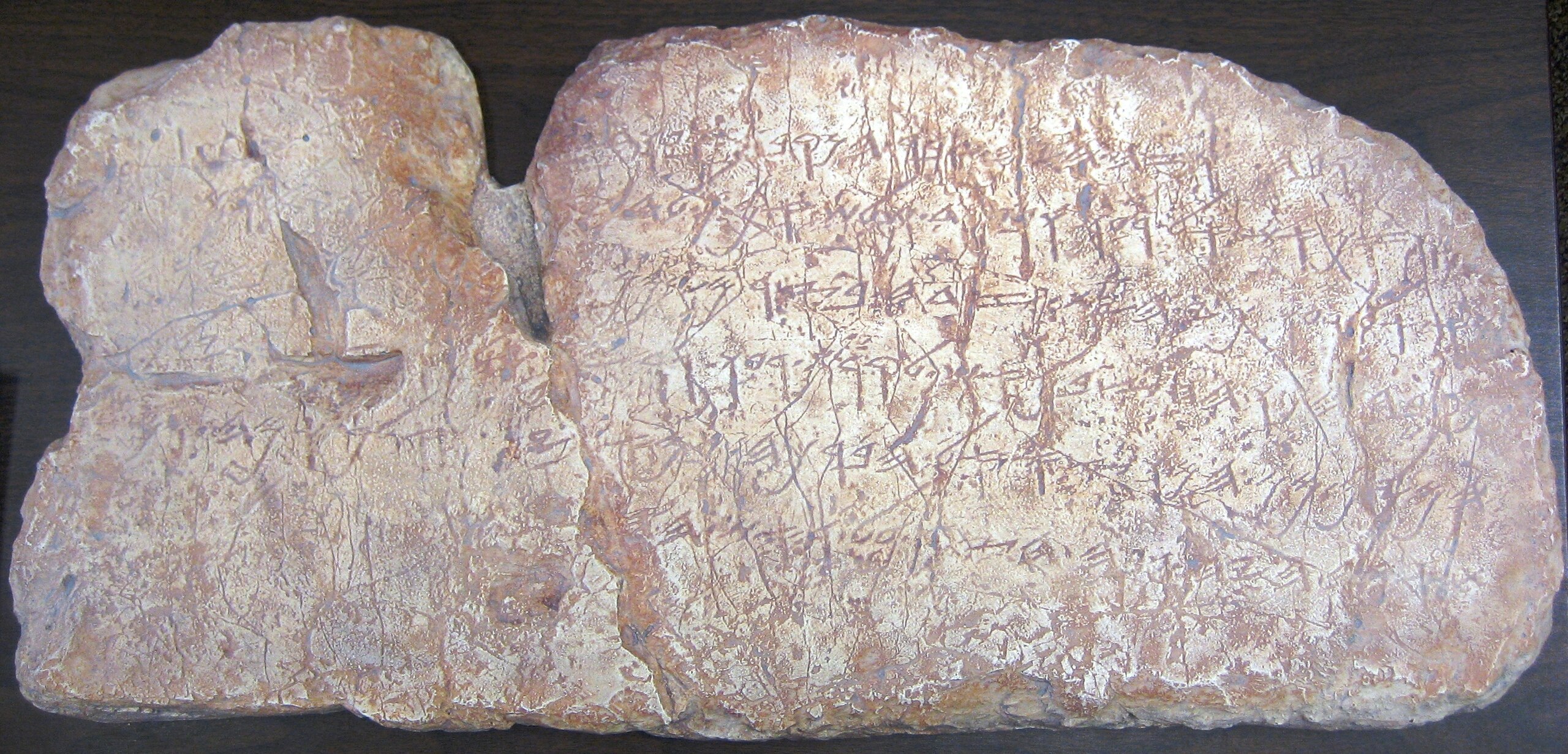

Considering the resources available at the time, Hezekiah’s Tunnel was an extraordinary engineering feat. Two teams of diggers were tasked with excavating a channel to connect the Gihon Spring with the Pool of Siloam. Less than 400 meters separate both places. Yet the tunnel stretches for more than 533 meters. Several times the workers had to correct their course, sometimes guiding themselves by the sound of the other team’s pickaxes. That is why the tunnel winds and zigzags beneath the ground of the ancient City of David. An inscription carved by the workers themselves immortalizes the moment when the two teams finally met.

“ …the tunneling was completed…

while the hewers wielded the axe, each man toward his fellow…

and there was a flow of water from the spring to the pool… “.

Although neither Hezekiah nor any other high-ranking figure is mentioned in this inscription—which only expresses the enthusiasm of workers and engineers who were proud of their achievement—the very act of digging a tunnel to divert the waters of Gihon fits perfectly with the biblical account narrated in the Second Book of Chronicles:

“There came Sennacherib, king of Assyria. He invaded Judah and besieged the fortified cities, intending to breach and take them. When Hezekiah saw that Sennacherib was coming with the intention of attacking Jerusalem, he took the advice of his princes and warriors to stop the waters of the springs outside the city; they promised their help (…….), for they said, “Why should the kings of Assyria come and find an abundance of water?” (2 Chronicles 32:1-4)

In 701 B.C., Sennacherib had raised a formidable army to bring the vassal kingdoms of Syria back into submission. Damascus-Aram, Judah, and the Philistines were seeking an alliance with Egypt against Assyria. Sennacherib’s campaign, mentioned in several places in the Bible (Isaiah 36–37, 2 Kings 18–19, 2 Chronicles 32), is documented by Assyrian annals and archaeological discoveries.

“In the fourteenth year of King Hezekiah, Sennacherib, king of Assyria, attacked all the fortified cities of Judah and captured them. Hezekiah, king of Judah, sent this message to the king of Assyria at Lachish: “I have done wrong. Leave me, and whatever you impose on me I will bear.” The king of Assyria exacted three hundred talents of silver and thirty talents of gold from Hezekiah, king of Judah. Hezekiah gave him all the funds there were in the house of the Lord and in the treasuries of the king’s house. (2 Kings 18:13-15)

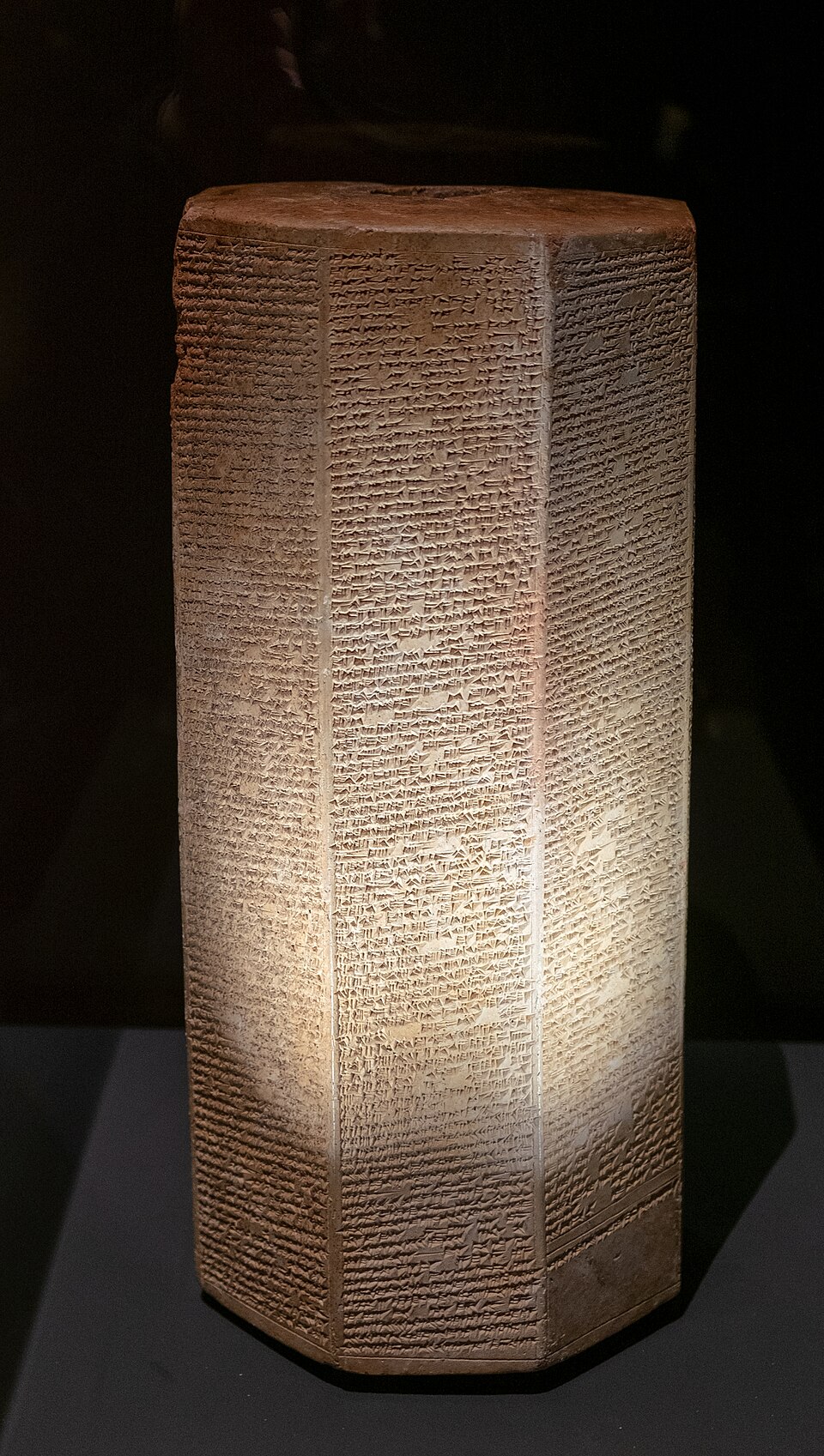

The annals of Sennacherib, written in Akkadian on clay prisms during his lifetime, relate more or less the same events:

“As for Hezekiah the Judahite, who did not submit to my yoke: forty-six of his strong, walled cities, as well as the small towns in their area, which were without number, by leveling with battering-rams and by bringing up siege-engines, and by attacking and storming on foot, by mines, tunnels, and breeches, I besieged and took (…). (Hezekiah) himself, like a caged bird I shut up in Jerusalem (Ursalimmi), his royal city.” (Taylor Prism)

There are certain discrepancies between the biblical accounts and the version recorded in Sennacherib’s annals. One of them concerns the amount of the tribute imposed on Hezekiah. According to Sennacherib’s annals, it totaled 800 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold, whereas the Bible speaks of 300 talents of silver and 30 talents of gold. Nevertheless, the biblical narrative does seem to confirm the exploits of the Assyrian king, who reduced most of the fortified cities of Judah to ashes.

Besieging Jerusalem was not worth the effort, from Sennacherib’s point of view. From Lachish, he contented himself with sending his cupbearer to the Holy City (2 Kings 18:17ff. and Isaiah 36:1ff.). The annals of the Assyrian king do not mention this episode, but they do confirm what the Bible tells us about Hezekiah’s uncomfortable position, shut up in Jerusalem “like a caged bird.”

What differs between the two accounts is how Jerusalem was saved. According to Sennacherib’s annals, it was at the cost of a heavy tribute and the handing over of Judah’s fortresses to Philistine vassal kings loyal to Assyria. According to the Bible, it was the work of the Lord, who first charged the prophet Isaiah with encouraging Hezekiah. Then, faced with the hardening of the Assyrian position (or the failure of negotiations?) and the blasphemous words of Sennacherib and his cupbearer, the Lord poured out his wrath upon the Assyrian camp:

“Then the angel of the Lord went forth and struck down 185,000 in the Assyrian camp.” (Isaiah 37,36)

As expected, the event does not appear in Sennacherib’s annals. It is possible, however, that the Assyrian army hastily withdrew from Judah because a conspiracy against Sennacherib was being plotted in Nineveh. There, his own “sons Adrammelech and Sharezer struck him down with the sword” (Isaiah 37:38). This final tragedy explains why, on Sennacherib’s bas-relief, the king’s face was erased by his assassins.

This bas-relief depicting the siege of Lachish adorned the walls of Sennacherib’s palace in Nineveh. It is now displayed in the British Museum, alongside Sennacherib’s prisms. Both artifacts complement and largely confirm the account of events as related by the biblical sources. All these historical sources—together with the spectacular archaeological discoveries of recent decades—converge to make Sennacherib’s 701 B.C. campaign one of the best-documented events in biblical history.

By Henri Gourinard