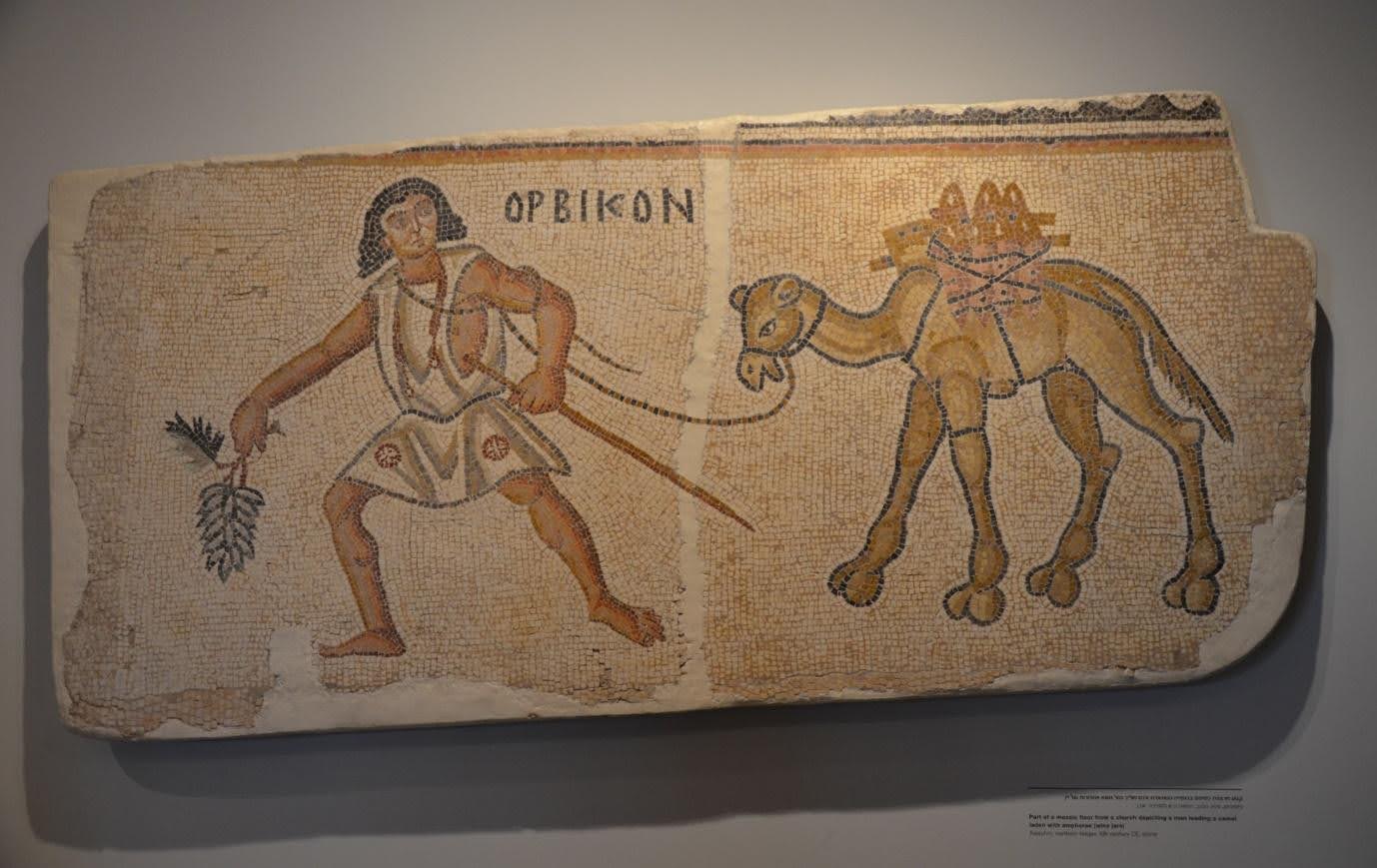

Fragment of a mosaic from a Byzantine church near Gaza depicting a man (perhaps a Bedouin?) leading a camel laden with wine amphorae. Kissufim, 6th century. Display location: Israel Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The 35th chapter of the Book of Jeremiah begins with a peculiar anecdote. The prophet Jeremiah, speaking in the first person, narrates an event that took place in Jerusalem at the time of the invasion of Judea by Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon (587/6 B.C.). God sent him to the leaders of the Rechabites, a nomadic tribe that had found refuge in Jerusalem, fleeing from the Arameans and the Chaldeans of Nebuchadnezzar’s army:

“The word that came to Jeremiah from the Lord in the days of Jehoiakim, son of Josiah, king of Judah:

Go to the house of the Rechabites, speak to them, and bring them to the house of the Lord, to one of the rooms there, and give them wine to drink.

So I took Jaazaniah, son of Jeremiah, son of Habazziniah, his brothers and all his sons—the whole house of the Rechabites. (…) 5I set before the Rechabites bowls full of wine, and cups, and said to them, “Drink some wine.

“We do not drink wine,” they said to me; “Jonadab, Rechab’s son, our father, commanded us, ‘Neither you nor your children shall ever drink wine:

Build no house and sow no seed; do not plant vineyards or own any. You must dwell in tents all your lives, so that you may live long on the land where you live as resident aliens.”

God clearly knew the customs of these Rechabites and was aware they would refuse all fermented drink, but He acts in this way so that this anecdote might serve as a prophetic gesture. If even these nomads obey their human ancestor, how is it that the people of Israel did not heed the voice of their own God when He told them not to resist the king of Babylon—His servant?

Let us return to the customs of these Rechabites. Although the prohibition on drinking wine brings to mind the prescriptions of Islam as we know them, it is merely an incidental rule. We know of pre-Islamic Arab tribes where consuming alcohol was not taboo. By contrast, what constitutes the essence of the nomadic or Bedouin ideal of life is the rejection of anything that might bind a person to a particular place. Not without a certain pride, the Rechabites respond to the prophet Jeremiah that:

“not building houses to live in; not owning vineyards or fields or crops. We live in tents, doing everything our father Jonadab commanded us (…)”

Freedom has its counterpart: poverty. Of this ethic of liberty, Diodorus of Sicily marvels when speaking of the Arabs (Library of History II, 48, 4):

“Thus, the Arabs inhabiting that territory, difficult to conquer, remain unenslaved; moreover, they accept no foreign leader and continue to preserve their liberty intact.”

In reality, the geographer refers to the Nabataeans, another nomadic people. They controlled the trade routes for spices and incense, from Yemen to the Mediterranean, passing through Petra. From Petra, their caravan route crossed the Negev desert, south of the Dead Sea. The Nabataeans soon exploited the salt of this sea and the bitumen (or asphalt) that floats on its waters, two highly valuable—and thus coveted—resources in the ancient world: salt for preserving food, bitumen for caulking the hulls of ships. At the end of the 4th century B.C., Demetrius Poliorcetes, son of one of Alexander the Great’s generals, Antigonus Monophthalmus (the One-Eyed), encountered the Nabataeans in battle while attempting to subdue the territories south of Syria to his father’s dominion. Although the outcome of the confrontation was uncertain, it was through this event that the existence of the powerful and prosperous Nabataean people reached the ears of the Greek world.

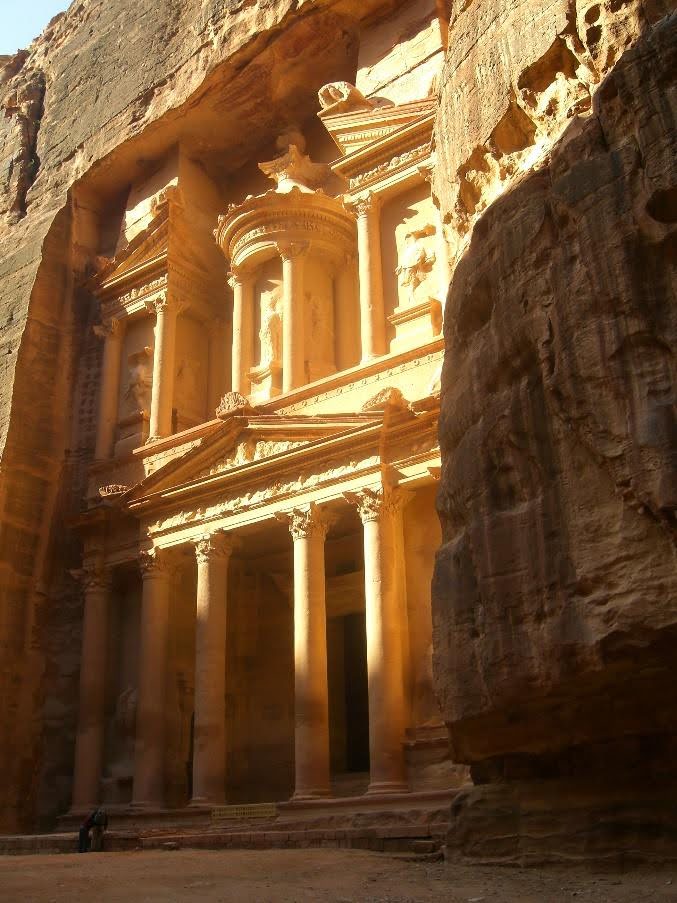

The site of Petra viewed from Jabal al-Madhbah. Henri Gourinard, 2010.

Diodorus continues, speaking of the “Rock” (Petra), where, according to him, the Nabataeans store their treasures. Is Diodorus correct? It is true that today one of the most prominent buildings in Petra is called al-Khazneh, meaning the treasury. But another is called al-Deir, meaning “the monastery.” Clearly, there was no monastery at that time. These are undoubtedly later designations. Petra was the only city built of stone—or, more precisely, carved into the rock—and it was a city for the dead. The living, however, adhered to the same nomadic ideal as the Rechabites: they lived in tents.

In the time of Jeremiah, the people of Israel had led a sedentary life for centuries. They had conquered a capital—Jerusalem—erected a temple to their God and intensely cultivated the land. Governed by a king who levied taxes and raised an army, the Israelites could see their desire to live like any other nation fulfilled (cf. 1 Sm 8). The days of the Exodus were a distant memory!

Perhaps to prevent Israel from falling into the pride of believing they had achieved this situation through their own efforts, every male Israelite was required, before presenting offerings in the temple, to pray the following to recall their humble origins as nomads and foreigners (Deuteronomy 26:5):

“My father was a refugee Aramean who went down to Egypt with a small household and lived there as a resident alien (…).”

By Henri Gourinard